By Bob Iaccino

AT A GLANCE

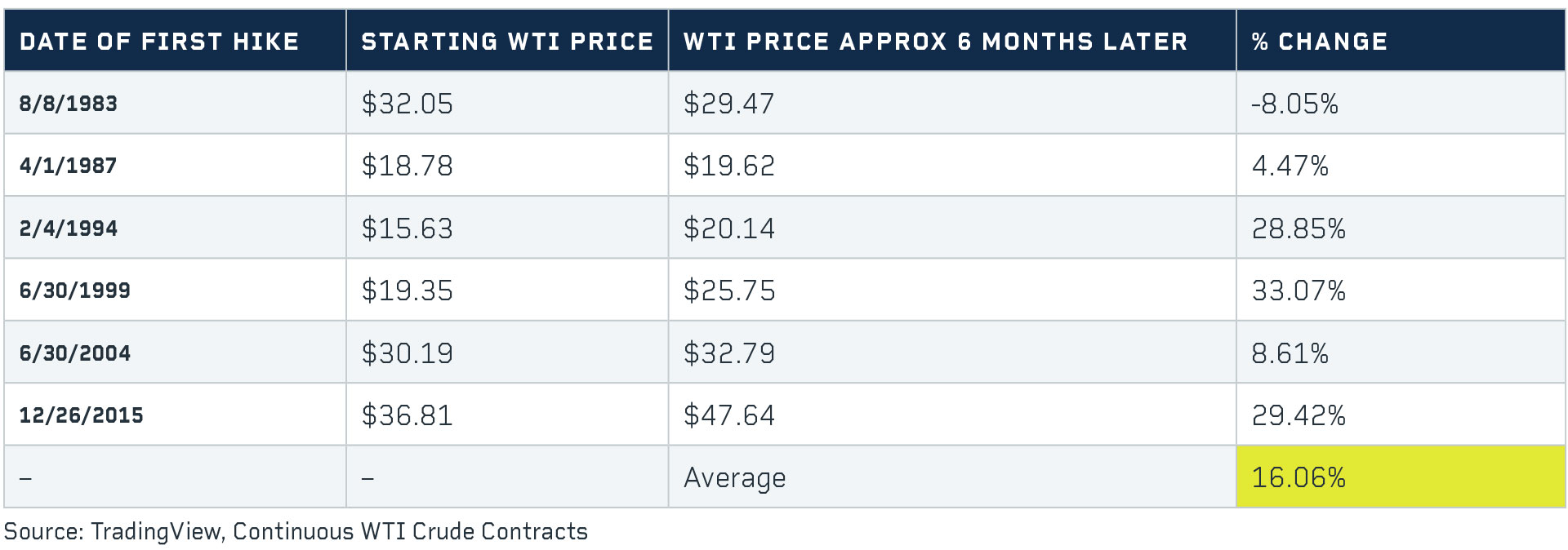

- Crude oil has averaged a 16.06% rise in price in the six months following the start of each of the Fed’s last six rate hike cycles

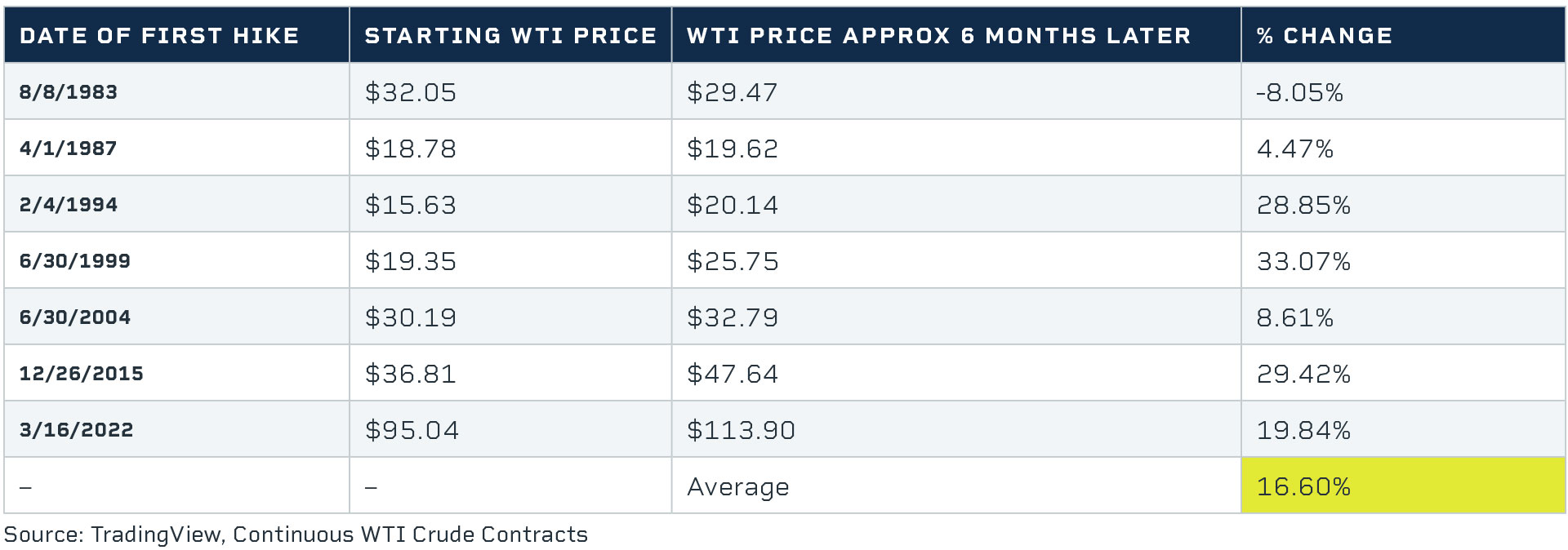

- In the first 10 days following the Fed’s March announcement of a 25 bps rate hike, WTI front month crude oil prices rose almost 20%

The FOMC’s latest rate hike cycle has begun, following the March 15-16 meeting in which the Federal Reserve hiked rates 25 basis points (bps). In the week after the announcement of the rate hike (through March 25), WTI front month crude oil prices at CME Group rose almost 20%.

With these recent moves, it's interesting to look back at what has happened to the price of crude oil historically during past rate hike cycles. Going back to August 1983, there have been six rate hike cycles in the U.S. The Fed’s FOMC raised interest rates a varied number of times for different lengths of time during these cycles, but all of these periods included at least two rate hikes. In the six months following the first hike of those cycles, crude oil has averaged a 16.06% rise in price; it has risen in five of those six-month periods following the beginning of a hiking cycle.

If you include the first hike of this cycle and the move in the price of WTI since the hike, that average jumps to 16.60%.

So, does crude oil rise because of rate hikes, or is this just a coincidence born of circumstances with no causal relationship at all? The simple answer is… both.

When you see statistics like this, you might start to wonder if Fed actions can be the spark that drives a commodity’s price higher. In order to ask that question, it seems relevant to think about why the Fed is raising rates in the first place, and to do that, we must look at the Fed’s mandate.

The Fed’s mandate was brought about by economic events that occurred in the 1970s, a period marked by the presence of high inflation and high unemployment, otherwise known as stagflation. The Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977, which acted as a de facto addendum to the original Federal Reserve Act of the 1913 Congress, clarified the roles of the Board of Governors and Federal Open Market Committee, which included the goals of maximum employment along with moderate long-term interest rates and stable prices. This became known universally as the Fed’s “dual mandate." One of the tools they use to achieve their dual mandate is the level of the Fed Funds Rate.

The latest reading of the unemployment rate is less than 4%, which many economists agree is either at or near full employment, so part one of the dual mandate (at least temporarily) has been achieved. However, part two – stable prices – is currently a concern. The most recent reading of year-over-year PCE price data shows inflation running at near 8%. Inflation growth at 8% is anything but stable, which means in order to achieve stable prices, the Fed has deemed it necessary to raise interest rates. But how do higher interest rates stabilize prices? Higher interest rates tighten financial conditions, and in theory, slow down the economy and reign in demand. Logically, lowered demand for the same number of goods over time means lower prices.

The hypothesis goes that if the economy slows, people will spend less in their daily lives and subsequently use less of everything, including gasoline in their cars and jet fuel in their planes, since people under financial pressure will be taking fewer trips. Business will become less busy which means those businesses would use less energy.

Looking at the table below, however, it seems like rising interest rates only affect crude oil prices slightly, at least in the midterm. In the 12 months following the first hike of the cycles going back to 1983, crude oil prices rose an additional 12.24% on average when measured from the six-month marker.

The data seems to show that while crude oil is one of the components that drives inflation, it may not be directly affected either positively or negatively by the actual change in rates in the short to midterm. There are many other factors affecting the price of crude oil, including geopolitics and sudden increases in supply or demand. It could just be that an integral part of inflation is the price of energy which, of course, includes crude oil. Typically, rising crude oil prices are either a significant component in the cause of broader inflation, or the rise in oil price is a function of a strong economy and greater demand.

The data seems to show that while crude oil is one of the components that drives inflation, it may not be directly affected either positively or negatively by the actual change in rates in the short to midterm. There are many other factors affecting the price of crude oil, including geopolitics and sudden increases in supply or demand. It could just be that an integral part of inflation is the price of energy which, of course, includes crude oil. Typically, rising crude oil prices are either a significant component in the cause of broader inflation, or the rise in oil price is a function of a strong economy and greater demand.

Crude oil prices do rise typically six months and twelve months after the start of a rate hike cycle, but that relationship may not necessarily be causal.

Original content provided by CME Group